Jane DeDecker

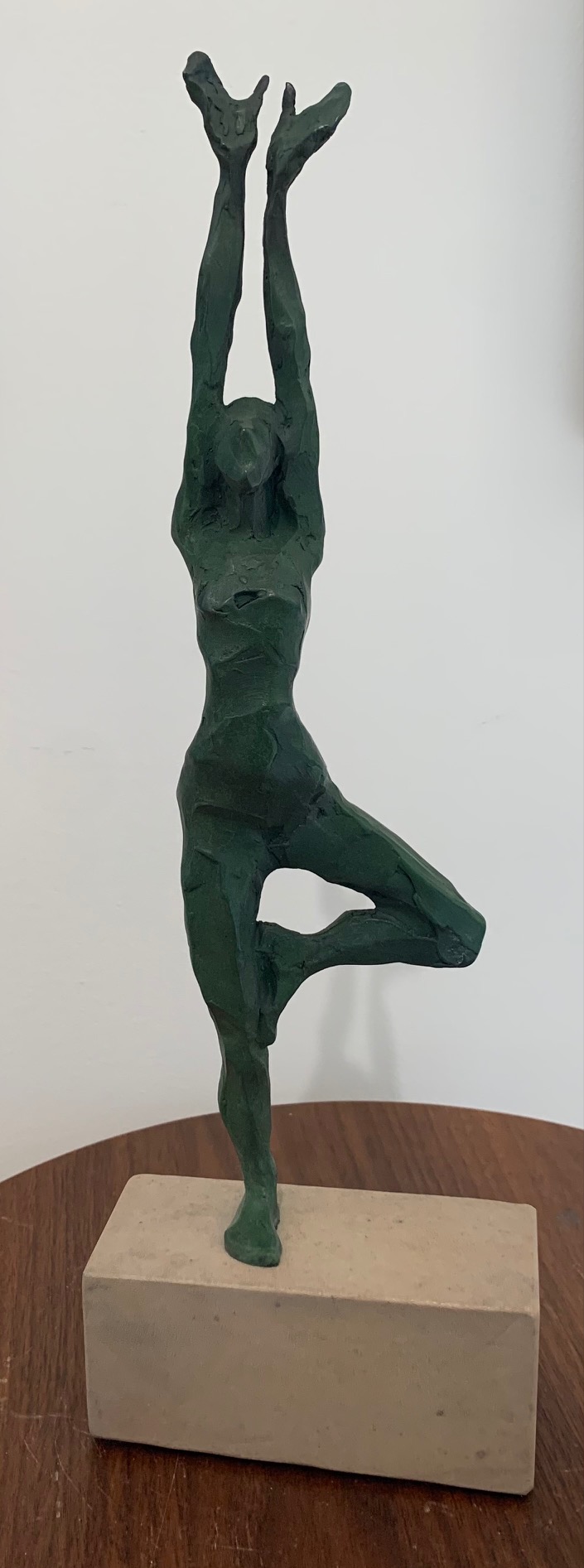

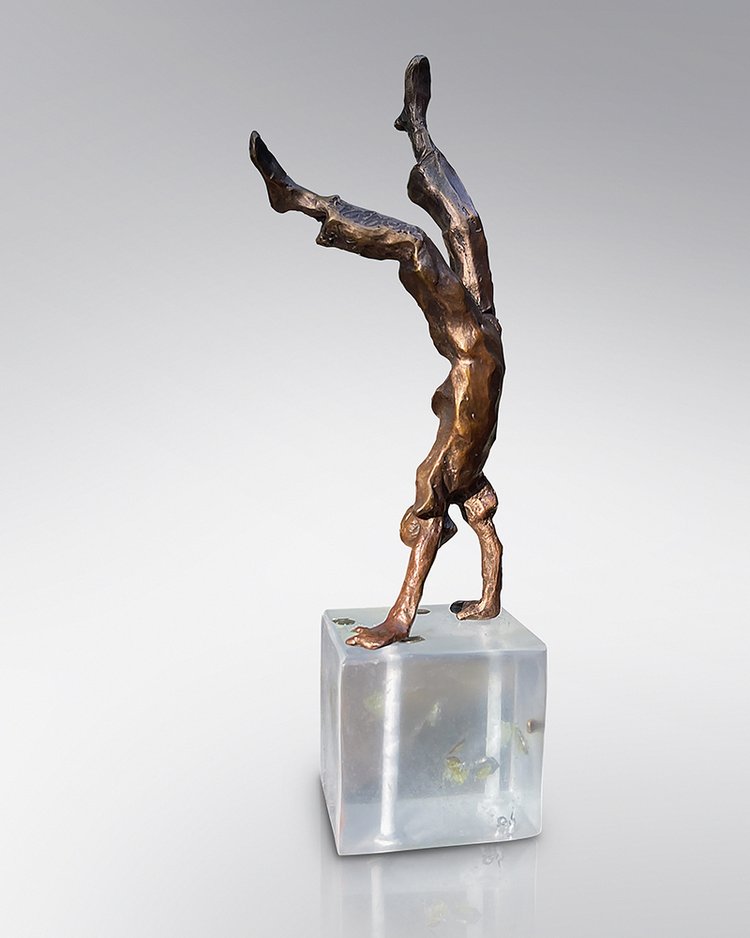

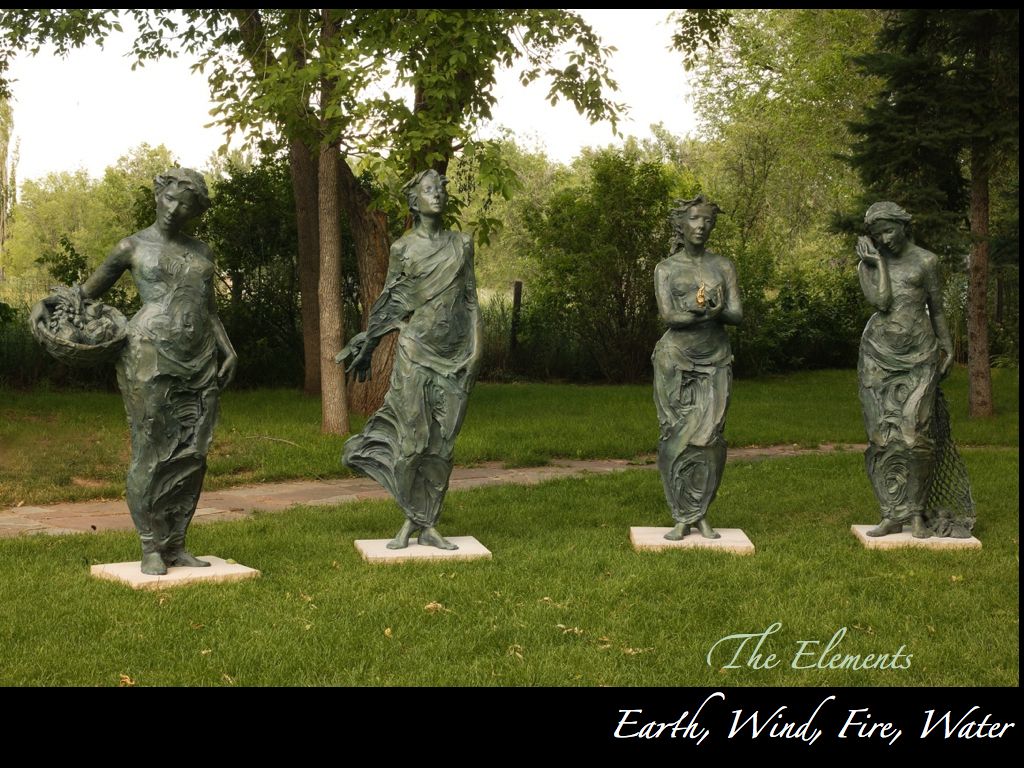

Jane DeDecker has been sculpting the human figure for over thirty-five years. She seeks to capture moments that reveal truths about the human condition, that, when stripped down to their essence, are understood intrinsically. As a figurative sculptor, she communicates emotional experience through lyrical compositions that move the viewer. DeDecker’s sculptures stop life in mid-sentence — somewhere between inhaling and exhaling – and gives it form. She tells a story through the simple moments that imprint our lives and define us.

Jane DeDecker has been sculpting the human figure for over thirty-five years. She seeks to capture moments that reveal truths about the human condition, that, when stripped down to their essence, are understood intrinsically. As a figurative sculptor, she communicates emotional experience through lyrical compositions that move the viewer. DeDecker’s sculptures stop life in mid-sentence — somewhere between inhaling and exhaling – and gives it form. She tells a story through the simple moments that imprint our lives and define us.

DeDecker was born in Marengo, Iowa in 1961. She grew up with nine sisters and brothers on a family farm, and her art work reflects a connection to nature, both the environment and human nature. As DeDecker works the clay, concepts emerge from memories and observations of life. Impressions of something felt, seen, or heard take three-dimensional form. A family rising with the dawn becomes a spiritual awakening. A woman worn thin by her burdens opens the possibility of a lightness of being. A man managing a wheelbarrow reminds us of the steadfast patience to balance life’s abundance.

DeDecker became a member of the National Sculpture Society in New York City in 1998 and a Fellow in 2007. She has placed over 175 life and monumental sized public sculptures in over thirty-three states. Some of the highlights of DeDecker’s installations include “Harriet Tubman” at the Clinton Library in Little Rock, Arkansas; “Albert Gallatin” at the National Park Service in Friendship Hill, Pennsylvania; “Emily Dickinson” at Converse College, in Spartanburg, South Carolina; “Can Can” at the Brookgreen Gardens in South Carolina; “In the Wings” at the Robinson Performing Arts Center in Little Rock, Arkansas; “Amelia Earhart” at the Earhart Elementary School in Oakland, California; “Sharing Discoveries” at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota; and “Who’s Watching Who” at the Meijer Sculpture Garden in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

DeDecker feels honored to be sculpting in a time when communities are investing in art to value what defines their unique history. Concepts for her sculptures are embedded in DeDecker’s research, and every sculptural gesture is a deliberate connection to the in depth digging she does to understand her subject. With every new challenge, DeDecker’s studio is covered in stacks of photos; copies of articles, journals, poems, and interviews; piles of clothing and physical artifacts. She searches for words and patterns to help her interpret the soul of her subject in a visual form. DeDecker is intrigued by more than capturing a likeness. She sculpts a piece until the research takes three-dimensional form and the viewer feels what her subjects must have felt. Until a portrait of Sojourner Truth says, “Ain’t I a woman?” she is not finished. Until she walks around and around a multiple figure piece, peering at it from all angles, is she satisfied that she has fully captured the intricate story of human interaction.

Along with her own sculptural interpretations of the human form, DeDecker equally finds fascinating commissioned projects. The interactive layer of working with a collector offers an artistic challenge to be the hands for the vision of a dedicated committee. DeDecker loves being the sculptural voice to commemorate an individual, celebrate a community, or memorialize an historical event. DeDecker partners with art counsels, elected committees, and families to ensure that a piece meets the vision as well as the budget and scheduled time-line. She works alongside structural engineers, landscape architects, and community members so that the work is installed and maintained with integrity.

DeDecker’s most ’recent commission, “On the Banks of Sugar Creek” reveals the connection between artist, community, and installation site. To commemorate 125 years of the Thompson Child and Family Focus organization, DeDecker sculpted a composition that warmly reminds us to take time to sit down with children – just listening to a child can be life- changing. DeDecker read notes from the founder of the organization, Edwin Osborne, to search for his passion and intent. In his journal, Osborne wrote about the many orphaned children after the Civil War, and the urgency to not only give these children a home but to preserve their childhood. He wrote that the smell of strawberries took him back to his own childhood memories. Jane also read the recollection of many of the orphans who wrote about time spent at the creek playing in the muddy water. In her piece, DeDecker depicted Osborne sitting next to children on the banks of the creek, at the original site of the orphanage. The shoes are lined up near the creek, in the same way you might find a neat row of shoes inside the front door at home. Osborne leans back, and time stands still for a moment as he sits with the children. Listening. One boy holds a leaf filled with strawberries. Another boy has his hands folded in a way that mimics his mentor. A young girl wiggles the mud between her toes. DeDecker’s final composition not only expresses the history of the foundation, but preserves the heart and soul of its dedication to children.

DeDecker manipulates clay with painterly brush marks, with careful attention to her intent. Under her hands, there is a fluidity in clay that echoes the human form. Her work is not static, nor is it a finished thought, but rather tied to a moment in time and place that reflects the unfinished story that is our humanity. The permanence of her sculptures cast in bronze drives her to respect the message she leaves behind – positive affirmations about life.